But the team, says Edge, still needed to cool the water around the reactor to stop a complete meltdown. Radiation levels around the plant began to rise and pressure levels began to drop. In teams, the workers went into the plant and attempted to open the vent. And they don't really know where they're going." "So they don't know how badly the radiation levels will be in the reactor building. "What they are doing is walking into the unknown," he says.

#JAPAN NUCLEAR REACTOR MELTDOWN FULL#

They worked in relay shifts, going into a pitch-black, hot environment in full hazmat suits where the radiation equipment was not working.

#JAPAN NUCLEAR REACTOR MELTDOWN HOW TO#

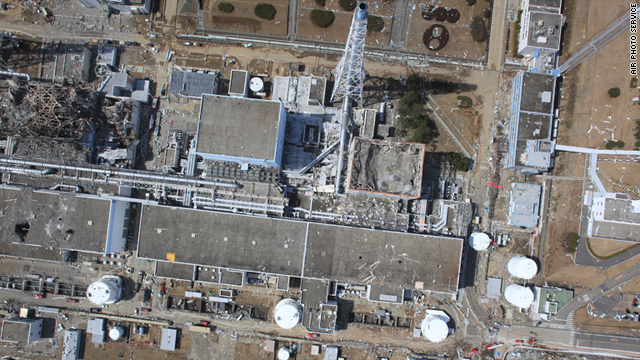

The plant workers - all of whom volunteered - figured how to manually vent the radiation, at great personal risk to themselves, says Edge. His argument is that he looked the plant manager in the eye, and he developed an understanding with him that was crucial to the functioning of the emergency response over the next few days. "The prime minster says he did a crucial thing that morning. A lot of people said, 'What can you achieve by landing in the middle of a disaster?' " says Edge. The prime minister, meanwhile, decided to go to Fukushima Dai-ichi and landed in a helicopter at the site. "He made the decision to leave," says Edge. Edge describes one resident who lived 2 miles from the plant and didn't know whether to continue to search for members of his immediate family or escape to a safer place with his young daughter. The surrounding communities were also terrified. But at the plant, the venting wasn't happening because the workers were struggling to figure out how to do it, says Edge. Then-Prime Minister of Japan Naoto Kan had given the orders to vent the radiation and was waiting for news that the reactors had been vented. Meanwhile, officials at the utility company that owned the reactor and officials in the Japanese government were watching the disaster from Tokyo. "What you have throughout that night is the workers pulling out the blueprints of the plant, going back to square one and trying to work out, there and then, in the middle of a nuclear disaster, how to vent a nuclear reactor," he says. They do not know what is happening inside the nuclear reactor. "Not only do they have no power for the cooling systems, they have no lights for the instrumentation. "It must have been horrific for them," says Edge. He tells Fresh Air's Dave Davies that after the earthquake and tsunami hit, power went out in Fukushima Dai-ichi, leaving the remaining workers stranded in the dark. His new Frontline documentary chronicles what happened to those plant engineers, as well as what happened to the small corps of workers who entered the power plant in the days after the disaster.Įdge talked to reactor inspectors, Fukushima residents and nuclear scientists in the Japanese government to piece together Inside Japan's Nuclear Meltdown, which premieres at 10 p.m. Investigative reporter Dan Edge wanted to find out what it was like for the workers who were inside the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant when the crisis began. In the days after a tsunami crippled Japan's Fukushima power plant almost one year ago, a small group of engineers, soldiers and firemen risked their own lives to prevent a complete nuclear meltdown.

After the earthquake, workers were sent inside Reactor 1 at the Fukushima plant to release some of the pressure building up inside the reactors.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)